Sewanee: University of the South

(SEWANEE, TENNESSEE)

Purpose of the Project

Sewanee: University of the South is located on the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee. The team’s project, initiated by student leaders, sought to uncover and share the hidden history of African-Americans in Sewanee and the surrounding region. The team hoped to expand the impact of a broader initiative sponsored by the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race and Reconciliation, which was created to uncover, explore, and reconcile Sewanee’s “historical entanglements with slavery and slavery’s legacies.” Since 2017, the Roberson Project began to investigate the University’s history with slavery and the Lost Cause, aiming to provide a better understanding of Sewanee’s past.

The team’s student leaders were Bonners who worked with the Roberson Project. The team partnered with Roberson to build relationships with Sewanee’s Black community, conduct interviews, collect oral histories, document Sewanee’s founding fathers’ connections to slavery, and create a platform to share stories from Sewanee’s untold Black history and current residents. The team sought to address three communities: (1) the residents of the historically Black neighborhoods of Sewanee and their descendants; (2) present and former students of Sewanee who are unaware of the indispensable contributions of generations of African-Americans to Sewanee; and (3) members of their surrounding communities who they hope can learn about and appreciate the significance of African-American history in this region.

“Each of these groups plays an important role in preserving the history of the St. Mark’s community and ensuring that their contributions to the University will be acknowledged and their presence in the greater Sewanee community known. We plan to work together to make changes in the physical environment, capture these stories and histories, and integrate them into our curriculum and four-year plan so that this part of Sewanee’s history is known to every incoming student and honored for every former student for whom this community was integral to their success and survival at Sewanee,” the team wrote in their proposal.

Meet the Team Leadership

Delana Turner is a rising sophomore at Sewanee: the University of the South from Hyattsville, Maryland. Delana, a Bonner Leader, is majoring in Political Science. She interns with the Roberson Project, doing historical work to investigate the university's ties with slavery and slavery's legacies and how those have impacted the way the university operates. “I really wanted to be part of the change that this university, along with many other places, so desperately needs,” she said.

Growing up, Delana knew she always wanted to help others, especially by pursuing social justice work. After her time at Sewanee, she hopes to pursue graduate school, earning a master’s and Juris Doctor in Law to build the communities in which she lives and works. “This experience – I'm going to hold it for the rest of my life because it's already significant to do work with the community, but this kind of work really resonates with me because that community has been wronged,” Delana said.

Noah Shively is a rising sophomore at the Sewanee: the University of the South majoring in Chemistry on a pre-med track from Fort Myers, Florida. Noah, also a Bonner Leader, is a member of the Sewanee Conscious Investment club, and interns with the Roberson Project along with Delana.

Noah was active in social justice efforts while in high school, participating in the March For Our Lives campaign, serving at HIV clinics, among other volunteer roles. When he began to understand the racial history of the Sewanee area through tours, seminars, and conversations, Noah was motivated to address the glaring issues of the lack of historical representation of Blacks and African Americans. “I just wanted to be a part of that conversation that was happening,” he said.

Partnership with The Roberson Project

The Roberson Project’s name memorializes the late Professor of History, Houston Bryan Roberson, who was the first tenured African American faculty member at Sewanee and the first to make African American history and culture the focus of their teaching and scholarship.

“We of the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation are pleased and excited to be teaming up with the Bonner scholars here at Sewanee to work on a project that should contribute significantly to our efforts to encourage racial healing in our community,” leaders said in a letter of support regarding the development of the team at Sewanee utilizing Racial Justice Community Funds for research in the area.

Since 2017, the Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation has been working to investigate the University’s entanglements with slavery. The Roberson Project served as the partner and sponsor for the team.

About two years ago, the Roberson Project started on an initiative to work with local African-American residents and their kin and descendants to build a Black Community Digital Archive. They have accomplished this aim by organizing several digitization fairs, bringing together people in the community to let them scan their family artifacts, recording their oral histories, and sharing their experiences on a new map of the town that marks the places and spaces of importance unique to them. This has been done in an effort to update the University Archive, which has consisted almost exclusively of the materials and artifacts of Sewanee’s White residents and students.

“The Bonner students have proposed to begin the work of building a heritage trail through Sewanee’s historic Black neighborhood while working in close partnership with the resident stakeholders of the neighborhood. That way the project realizes our goals for true sharing of power and control over how this community’s memory is preserved.”

Navigating political tensions of town and gown

Challenges and difficulties arose for the student leaders whilst working in conjunction with the University while also attempting to build relationships within the community that was harmed by University practices. “We had to embrace humility and patience while learning to effectively communicate with Black community members about our and the University’s motivations and intentions,” they shared. The team said that they felt supported by Sewanee administrators, who actively supported them to do the work, but that didn’t make their efforts less arduous.

“It's really hard to do it [historical work] because materials are sought after and categorized by who is in control of those archives, and our archives are predominantly white spaces. So a lot of the work in there is just, from a white perspective. So we don't have much material,” Noah said. “But I think the hardest part of it all is calling community members where you have to say that you are a Bonner working for the University of the South, and it's understandable that there is a lot of hesitation, and sometimes even just a dismissal.” The students focused in particular on rectifying those relationships.

REeducating the broader campus and BUILDING community

The team, in conjunction with the Roberson Project, was able to educate the community through several online lectures. One lecture focused on Sewanee’s founding Bishop Leonidas Polk and his legacy regarding slavery and the confederacy on April 13 2021. Other discussions and movie screenings confronted the history of racism within the community and America as a whole.

These events were a welcome opportunity to push past ignorance to informed action, shedding more light on the Roberson Project’s goals and giving them more support to achieve their goals of recognition of these community members. “It's just amazing to me how marginalized and disregarded this community was,” Delana said. “Like we know that certain places existed, but there's no record of it.”

Sewanee Team and Community Members pose with the float of Black History for the July 4th Celebration.

The team also organized campus participation in a Juneteenth Celebration and Soul and Jazz Festival with neighboring towns at St. Mark’s Community Center. For the July 4th Town Celebration, the team drew on the community members’ stories to create and include a float to commemorate local history of Black individuals and the Black Community. The float was designed like a photo album, and the opening book contained actual community members as well as photos.

“It was supposed to be this kind of symbol of history coming to life,” Noah explained. “We found out that even community members on the float were in pictures as little children in the scrapbook that we developed, and so they were able to help us out with that as well. It really meant a lot to them.”

learning to organize through storytelling

Something that was integral to the growth of the team and their abilities were various training sessions they attended with the Roberson Project and other advisors to teach them how to properly interview community members. They learned strategies for effective oral history work including about open-ended questioning, appropriate follow-ups, helpful body language and voice control were a part of learning how to successfully and sensitively interview someone about these personal topics.

“You learn how to divert and ask another question or if need be just end it, but you don't want to end it if you can help it. You also don't want to intrude because it's understandable that people are very protective over their oral histories and we need to be respectful of that,” Noah said.

The team shared the story of a particular community member who has felt underrepresented and hurt by the St. Mark’s Community Center, as well as the University. Initially, she had no interest in helping the team or participating in events such as the Fourth of July float.

“We had asked her to be a part of our float because there was information about how she felt that she was underrepresented and we wanted to have her represented on this float because she is very much a large part of supplying this history just like everybody else,” Noah explained.

The team was pleasantly surprised when the resident changed her mind, came to the event, and even brought more people with her, people who had not previously participated. The team was very encouraged that consistent relationship building could change perspective and spread inclusivity to those who have been previously excluded. “Fostering these relationships with community members has been the most important thing that we've done so far with this project,” Noah said.

MAPPING AN INCLUSIVE TRAIL with broader input

The team hopes to share these stories in a new trail and tour of campus that recognizes Black people’s history and place. They envision prerecorded oral histories available at future trail marker sites, so that visitors (including those with visual impairments) can listen and learn from the town's history in an accessible way. They are hoping to potentially have those whose stories are being told to be the voice in the recordings, bringing even more authenticity and centering of their personal histories. “We just want to make sure that Black history is just as well known as the White history and White contributions to this campus,” Noah said.

As the team continues to research and conduct interviews, they are wrestling through the necessary conversations and considerations regarding building the historical trail through Sewanee’s historically Black neighborhoods. On one hand, they would love to highlight and make available various stories, however, they want to accomplish this in a way that honors the community’s often overlooked needs.

“You start to realize that the trail that was mapped out, maybe isn't really the right one and then you have to ask the question, does the community want a trail going through them?” the team wondered. “There may be places that they do, and then maybe places that they don't and being really sensitive to that. We realize that there are more layers to it that we have to be considering and we have to take our time to make sure we're doing it justice.”

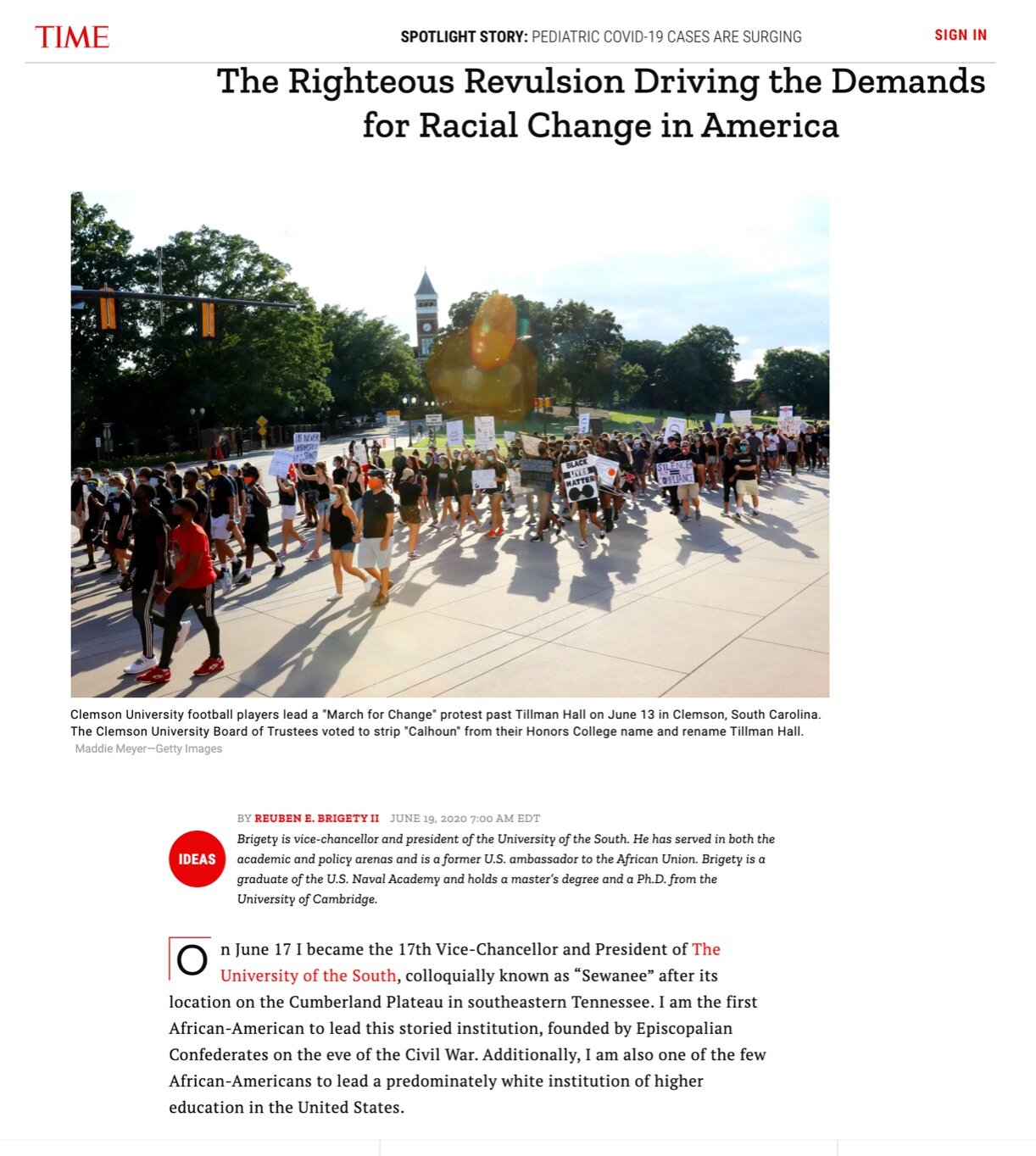

Reuben E. Brigety II, Sewanee’s Chancellor, writes about the University’s work to examine its past with the Roberson Project here for Time.

To achieve that balance the team is aiming to conduct more interviews with an intentionally diverse and wider range of people within the affected communities. “I think prior to doing this project, there was not much communication there. It was pretty frequently the same community members. So now we've expanded past that and we're getting in touch with people that have not shared their story at all, or didn't even know what this project was,” Noah said.

a road towards reconciliation?

The team expressed fulfillment in what they were able to complete so far, while also maintaining a clear drive and passion to push forward knowing that the work is incomplete. Their efforts and motivation moving forward do not come without precedent.

Newly appointed African American Vice Chancellor, Reuben E. Brigety II, has helped push the University of the South on a trajectory towards participation in the reparations movement, spurring national coverage as seen in Time Magazine and the Washington Post. The direction has garnered support and momentum from current students at Sewanee as they wrestle with removing the ties the University has from the previous veneration of the confederacy.

“Connecting with the community members and telling them that we want to commemorate their spaces by asking, ‘Tell us more about yourself and your life, about being marginalized by the University, etc.’ They were like ‘Wow, somebody actually cares about the experience I had back then.’ Hearing their voices, seeing their faces when they see that, yes we care about it even though previously the University didn't, to me has just been the biggest impact because we get the chance to change that narrative,” Delana said.

To learn more

To read and review the executive research summary from the Roberson Project regarding Sewanee’s institutional history check out this link.

For information about the Roberson Project, including its summer launch and archive, visit this link.